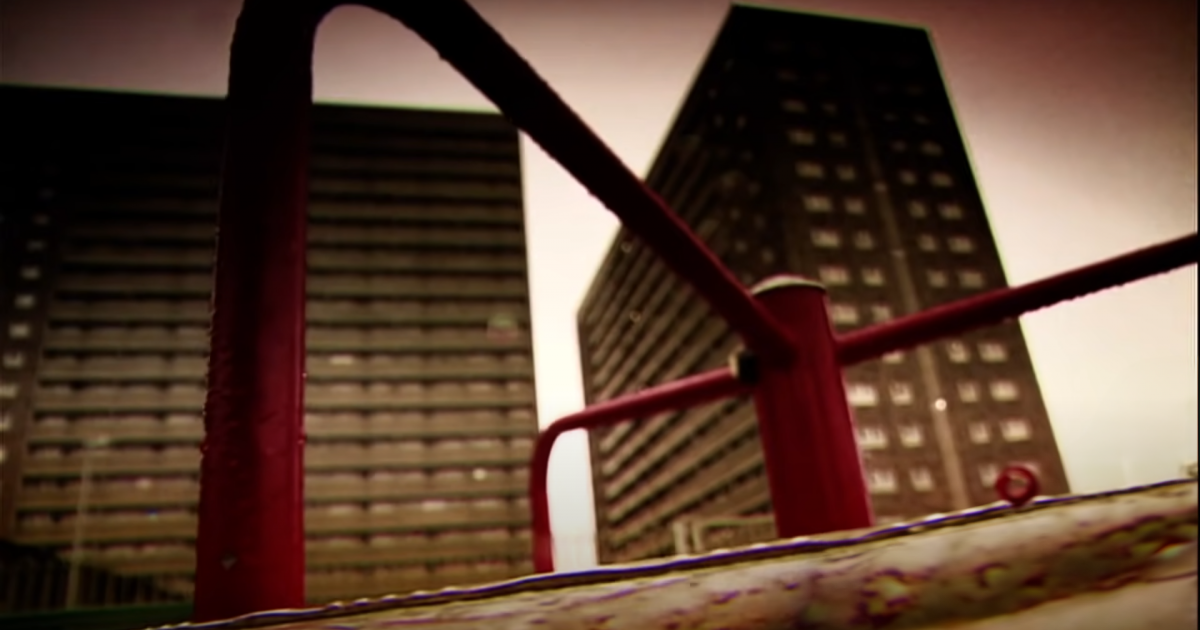

"No child should be living in poverty"

When MSPs debated Addressing Child Poverty Through Parental Employment, Maggie Chapman used her speech to challenge some of the myths of poverty and call for systemit change.

This is another debate that, in a just and compassionate world, we would not need to have. No child should be living in poverty, anywhere, and the fact that so many do, in a hugely prosperous country such as ours, is a source of deep collective shame.

We can speak glibly sometimes about equality, but there is no greater inequality than this: that whether or not a child goes to bed hungry and cold depends primarily on how much money their parents have. And that in turn largely depends, except for a privileged few, on what kind of work those parents do.

That, when we think about it objectively, is a ridiculous and incredibly unfair situation.

It’s one that we can mitigate to some extent with the Scottish Child Payment and other social security measures, and I’m proud of the part the Scottish Greens have played in those. But important as they are, and we know they are keeping many children away from the brink of poverty, they are not enough alone.

So, as this report demonstrates, addressing parental employment has to be an urgent part of our response. And for that response to be effective, we need some fundamental changes. We need to change some mistaken beliefs and assumptions. We need to change the way in which we view, value and deliver childcare. And we need to change our economy itself – what it does, what it enables, who it works for.

One myth is that parents aren’t already working. As the Poverty Alliance has pointed out, over two-thirds of children in poverty live in a household where at least one adult is in paid work. Yet that work pays too little, or covers too few hours, to meet a family’s basic needs.

That really is shocking. Whether we’re talking about deliberately exploitative employers, small enterprises themselves squeezed by financial pressures or care and transport deficits that limit availability for work, this is a failing system, not failing families.

That’s why it’s so important that Best Start Bright Futures aims not only to increase access to employment, but specifically to increase earnings as well. And that’s why fair work really matters, work that provides an effective voice for employees, opportunities to develop and learn, job security, human fulfilment and real respect.

And another myth is that all types of family are facing the same challenges. I share the disappointment expressed by Close the Gap that the committee didn’t choose to take a gendered approach to their investigation.

It is not an eradication of the existence or importance of fathers for us to recognise that most primary caregivers and the vast majority of lone parents are women, and that those women are encouraged to seek jobs in low paid, inflexible and undervalued sectors. On the contrary, acknowledgement of those realities allows us to see and articulate the particular challenges faced by single and caregiving fathers, which may often be less about financial pressures and more about societal attitudes and assumptions.

Secondly, we, collectively, need to change the way that childcare is seen, valued and provided. The recent funding announcement was very welcome, but this is a wider and deeper problem than childcare workers’ pay.

Childcare needs to be affordable, accessible and flexible, not limited to school hours, or to a traditional 9 to 5 working day.

With a decline in the number of childminders, family and informal networks often come forward to fill in childcare gaps. But for many these are unavailable, including where families move for work or study. The special challenges for student parents were rightly highlighted in the committee's report, and I urge all colleges and universities to follow the sensitive approach that some have pioneered.

We should recognise, too, that different children have very different needs; socially, developmentally, physically and emotionally, and that those needs change throughout their childhood and adolescence.

We need to employ our imaginations as well as our intelligence, recognising the many dimensions and relationships of our own lives and not expecting those of families in poverty to be any less complex or nuanced. I particularly commend the childcare vision and principles set out by Close the Gap and One Parent Families Scotland and hope to see them widely accepted and implemented.

Thirdly, we need to see fundamental changes in our wider economy. As the report wisely highlights, nothing short of a whole system approach will be enough. Inclusion Scotland and the Poverty Alliance have both outlined some of the most critical elements – the need for accessible, safe, and free public transport, 10-minute neighbourhoods, Living Hours provision and flexible and home working made available much more widely.

A just transition is desperately needed, away from the obscenity of an eight million pound pay package for BP’s chief, to a just, green economy that is at its heart an economy of solidarity and care. That’s not only about renewable technologies, important as they are, but about all the work that creates, builds and grows a healthy Scotland and a peaceful world.

I’d like to close by speaking directly to those families, to children in poverty and the parents who struggle daily to give them what they need and deserve. You are not invisible. You are not forgotten, and this is not your fault.